Economic Uncertainty Prevails as Vietnam Prepares to Host the 2019 Asian Games

Editor’s Note: In response to questions regarding whether the World Bank would financially support Vietnam’s plan to host the Asian Games in 2019, Victoria Kwakwa, the World Bank’s Country Director for Vietnam, said that the organization would not make a commitment to providing loans to construct event infrastructure. On Thursday, April 17th, Vietnam announced that it was pulling out as the host of the 2019 Asian Games. In explanation, the government cited a lack of preparedness and worries that holding the event would not be financially viable.

HANOI – Hanoi’s successful bid for the 2019 Asian Games (ASIAD) has created a heated discussion on the merits of the proposed organization plan and its economic benefits. Strong public opinion pressure has focused on the uncertain benefits of hosting the Games – in the past, Vietnam has been known to be less than wise in how it spends taxpayers’ money.

HANOI – Hanoi’s successful bid for the 2019 Asian Games (ASIAD) has created a heated discussion on the merits of the proposed organization plan and its economic benefits. Strong public opinion pressure has focused on the uncertain benefits of hosting the Games – in the past, Vietnam has been known to be less than wise in how it spends taxpayers’ money.

In response to this pressure, Vietnam’s Prime Minister, Nguyen Tan Dung, has required the Minister for Culture, Sports and Tourism to issue as soon as possible the official proposal for operating the event. The Prime Minister has emphasized that the government still supports the Games, but the final decision will depend on the feasibility of the proposal put forward.

RELATED: Dezan Shira & Associates’ Asia Business Model Comparison Services

RELATED: Dezan Shira & Associates’ Asia Business Model Comparison Services

In 2012, Hanoi defeated Surabaya (Indonesia) in the competition to be named the host city of the 2019 Asian Games. Dubai (UAE) was also a front runner in the competition until the city withdrew its bid because the federal government did not agree about the feasibility of hosting the Games.

RELATED: Hanoi GDP on the Rise in First Quarter of 2014

How much did you say?

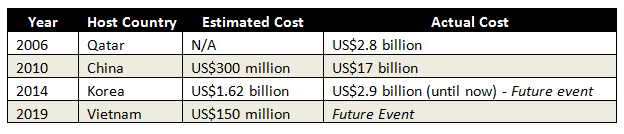

According to the proposal submitted to Vietnam’s government in 2011, the total cost of the Games was estimated to be about US$300 million – 96 percent of the cost was to be covered by the national budget and the remaining costs were to be covered by the private sector.

However, the Ministry of Finance has criticized the 2011 proposal, saying that the estimated amount would be an undue burden on the national budget and that the actual total cost would turn out to be much higher than the given estimate. Thus, the Ministry of Finance suggested not hosting the Games until Vietnam was financially capable of operating the event and was able to create a commercially desirable event to attract corporate sponsors.

RELATED: Has Vietnam Fallen into the Middle Income Trap?

In response to the Ministry of Finance’s criticism, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism cut the estimated cost of the Games to US$150 million and introduced a new capital mobilization rate, which flipped the previous payment structure on its head: the national budget would cover 28 percent of the total cost and the private sector would be responsible for the remaining 72 percent. This new proposal was presented to the Committee for Culture – Education – Children’s Youth (CCECY) and the National Assembly on March 19, 2014.

Not a winning history

Despite the revised cost estimate and payment structure, one of the main underlying issues was still not addressed – the actual cost of the Games upon completion. The committee members strongly suspected that the adjusted cost of US$150 million was an inadequate amount with which to fund the event.

It seems clear that the estimated cost put forward does not reflect the actual cost borne by previous hosts of the Asian Games:

Like the Olympic Games, the Asian Games often provide a doubtful economic return to the hosting cities. Previous hosts of the Olympic Games, such as Athens and Montreal, found that ballooning costs almost bankrupted what were well functioning cities before the arrival of the Olympics. Even China has found it hard to find uses for all the new buildings it created for their Olympic Games.

No doubt with an eye on these previous difficulties, after consideration, the CCECY felt that, due to the limited national budget and the growing number of requests for new residential construction to support the Games, Vietnam should pull the plug on the 2019 Asian Games.

No take-backs?

In response to this decision, there have been many in Vietnam who have voiced concerns about the potential hit to the country’s international prestige if it were to pull out of hosting the Games. However, Mr. Le Dang Doanh, former manager of the Central Institute for Economic Management, has argued that the international prestige of a country does not depend on the number of medals it wins in a sports competition, but instead comes from the level of its economic growth. He explained that hosting the Asian Games would increase public debt, which would hurt Vietnam’s prestige in the eyes of international investors.

While the Asian Games can bring some opportunities for economic growth, the current economic and social infrastructure in Vietnam could prevent the country from making proper use of these opportunities. The Asian Games can only promote economic growth if the country’s citizens as a whole, not a small group of people, benefit from the event.

The role of the private sector in infrastructure and service delivery projects must be prioritized in order to guarantee the spread of benefits to different groups of citizens. “However, this prospect is often unattainable because these projects often fall into the hand of state-owned enterprises,” says Nguyen Duc Thanh, manager of the Vietnam Centre for Economic and Policy Research. “Considering the current investment climate, the operation of the games not only creates a non-competitive market, but also fosters ineffective state-owned enterprises.”

Mr. Thanh added that “Vietnam is not committed to economic reform enough in order to make use of the 2019 Asian Games to speed up its economic restructuring process.”

As the criticisms continue to pile up against hosting the Asian Games, it is clear the government will have to make a difficult decision very soon.

Dezan Shira & Associates is a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam in addition to alliances in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand as well as liaison offices in Italy and the United States.

For further details or to contact the firm, please email vietnam@dezshira.com, visit www.dezshira.com, or download our brochure.

You can stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends across Vietnam by subscribing to Asia Briefing’s complimentary update service featuring news, commentary, guides, and multimedia resources.

Related Reading

A Guide to Understanding Vietnam’s VAT

In this issue of Vietnam Briefing, we clarify the entire VAT process by taking you through an introduction as to what VAT is, who and what is liable, and how to pay it properly. We first take you through the basics of VAT in Vietnam before taking you deeper into the topic. Additionally, we provide updates on the new changes to the VAT process and explain how they will impact your business. The magazine is out now and will be temporarily available as a complimentary PDF download on the Asia Briefing Bookstore until the end of April.

Vietnam Set to Open First Online Bitcoin Trading Floor

Cheers to Vietnam: Competition on the Rise in Vietnam’s Beer Industry

McDonald’s Supersizes its Business in Vietnam

Vietnam’s Agricultural Sector Sees Strong Growth Thanks to FDI

- Previous Article The Rich List: Number of Vietnam’s Ultra-High Net Worth Individuals to Increase

- Next Article Ho Chi Minh City Government Presents Clear Plan for Future Economic Growth