Transshipment and Origin Risks: How Vietnam-Based Businesses Can Stay Compliant

The US administration has heightened its scrutiny of transshipment practices, viewing them as a factor behind “imbalanced trade” with key partners such as Vietnam, believed to serve as a rerouting channel for Chinese-origin goods into the US market.

In July 2025, the United States imposed a 20 percent tariff on a range of Vietnam’s exports and a 40 percent duty on goods identified as transshipments from third countries. While speculation about Washington’s intent to address the issue had circulated before the announcement, the steep 40 percent rate still caught many observers off guard.

In the aftermath, industry groups and trade experts have urged restraint, noting that the US administration has yet to issue detailed guidance on how transshipment cases will be identified. The situation, therefore, remains fluid and open to interpretation.

Nevertheless, proactive preparation is far from excessive in this evolving environment. Businesses that implement effective compliance and traceability measures can better protect themselves against the potential fallout of the US’s shifting tariff regime. In fact, with the right strategy, the new tariffs could even serve as a competitive differentiator – favoring firms with genuine manufacturing footprints in Vietnam over those merely rerouting goods to circumvent US duties.

Is Vietnam a transshipment point?

Washington heightens scrutiny amid expanding Vietnam-US trade

Testifying before the US Senate on June 4, 2025, Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick spoke of growing US concern over Vietnam’s trade practices, asserting that the country has become “just a pathway of China” to the American market. Lutnick noted that Vietnam “buys US$90 billion from China,” then “marks it up and sends it to the US,” emphasizing that Washington is “absolutely seeking reciprocity,” but “when they’re importing from China and sending it to us, they’re not.”

According to US officials, a segment of manufacturers that once operated in China is believed to have established shell entities or light assembly lines in Vietnam to capitalize on its preferential trade terms with the United States. These firms allegedly re-export goods under Vietnamese origin, with minimal processing, to bypass elevated US tariffs on Chinese-made products.

There is some validity to these concerns. Vietnam has become an increasingly attractive base for companies seeking to diversify supply chains and mitigate exposure to US-China trade tensions. The data reinforces this trend: since the onset of the trade war in 2018, Vietnam’s exports to the US have surged, and the bilateral trade deficit has widened. US Census Bureau statistics show that between 2002 and 2018, Vietnam’s exports grew steadily – from US$2 billion to US$39 billion, averaging around 6 percent annually. From 2018 to 2024, however, growth accelerated sharply to about 21 percent per year, reaching US$123 billion.

Still, the transshipment narrative tells only part of the story. A Harvard University study (2025) found that from 2018 to 2021, only 8.8 percent of Vietnam’s export growth to the US – measured at the provincial level – could be attributed to rerouting. Much of this rerouting was linked to new Chinese investors relocating to Vietnam to rebrand Chinese-origin products as Vietnamese. The phenomenon is geographically concentrated along key northern transport and industrial corridors: the Noi Bai-Lao Cai Expressway linking Hanoi’s main airport to the Chinese border, Bac Giang in the northeast (a major electronics hub), and Lang Son, another strategic border province.

Findings from Vietnam’s inspections

Since 2020, as the first phase of the US–China trade war intensified, Vietnam’s General Department of Customs has stepped up efforts to combat origin fraud and illegal transshipment. These violations have become increasingly sophisticated as Vietnam has deepened its integration into global trade networks.

Authorities have uncovered multiple cases involving goods, such as electronics, garments, footwear, bicycles, wood products, iron and steel, and solar panels, being imported from China for minimal processing before being re-exported to the United States under “Made in Vietnam” labels. Customs data at the time showed that 24 out of 76 inspected cases involved false origin declarations, resulting in the seizure of 3,590 bicycles, over 4,000 sets of bicycle components, and 12,000 sets of kitchen cabinet accessories. In one instance, a company established in 2018 in Ho Chi Minh City was found to have issued fraudulent certificates of origin to approximately 30 enterprises, with total export values exceeding VND 600 billion (US$25.8 million).

Viewed in this context, US concerns over potential rerouting through Vietnam are not unfounded. However, the country also presents legitimate opportunities for manufacturers pursuing a “China Plus One” strategy, supported by its improving industrial base and expanding trade network.

Given that US authorities have yet to issue clear guidance on identifying transshipments subject to the 40 percent tariff, exporters are best advised to maintain strict compliance with existing US rules and ensure that their Vietnam-origin certifications are properly documented and verifiable. Going forward, diligent recordkeeping, transparent supply chain documentation, and proactive internal audits will be essential tools for mitigating regulatory and reputational risks.

What does US Customs allow?

What is ‘illegal transshipping’ under US regulations?

On July 16, 2025, the Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (CTPAT) issued an alert regarding illegal transshipping, outlining the types of transshipment practices that violate US trade regulations. The alert defines “transshipping” as “the process of transferring goods from one mode of transportation to another (often from one vessel or port to another) during their journey from origin to destination.”

CTPAT emphasized that transshipment is legal and widely used in international logistics. However, it becomes illegal when used deceptively to evade tariffs, sanctions, or trade restrictions. Specifically, a transshipment is deemed unlawful if it enables circumvention of US trade enforcement measures, including:

- Avoiding antidumping or countervailing duties (AD/CVD): Exporters route products through third countries to mask the original country of origin, particularly when that country is subject to high duties or quotas. Here is an example: Country A (e.g., China) faces high US tariffs on wooden bedroom furniture. A Chinese furniture manufacturing company ships its product to Vietnam instead of shipping it directly to the US. Once in Vietnam, the product is re-labeled as “Made in Vietnam”, and it may be lightly processed or repackaged. The goods are then exported to the US as Vietnamese goods to avoid US tariffs.

- Evading Section 301 or Section 232 Tariffs: Especially relevant for goods from China, where exporters try to relabel Chinese-origin products as originating from nations without such tariffs.

- Exploiting Free Trade Agreements (FTAs): Some bad actors attempt to falsely claim preferential tariff treatment (e.g., under USMCA or CAFTA-DR) through fraudulent certificates of origin or minimal processing.

Additionally, illegal transshipments also involve intentionally undervaluing goods, misclassifying items, or reporting incorrect quantities to reduce tariff liability (false declaration).

US provisions on the Country of Origin Marking

Under US Customs and Border Protection (USCBP) regulations, all imported goods must be clearly and permanently marked in English with their country of origin, unless specifically exempted. The primary purpose of this requirement is to ensure that the final US purchaser is informed of the product’s place of manufacture. Acceptable methods of markings include branding, stamping, molding, or printing, provided the mark remains legible and visible under normal handling until the product reaches the buyer.

The country of origin is defined as the location where a product is manufactured, produced, or grown. However, the origin may change if the product undergoes substantial transformation – that is, when a new article emerges with a distinct name, character, or use from the original input materials. Until further bilateral guidance is released, businesses should adhere strictly to these USCBP provisions to avoid the risk of misclassification or unintentional transshipment labeling violations.

How to comply with Vietnam’s rules of origin

To mitigate transshipment risks and maintain access to preferential tariffs, Vietnam-based manufacturers and exporters must strengthen compliance with the country’s rules of origin (ROO). These rules define when a product is considered “Vietnamese” under various trade agreements, a designation that determines whether it qualifies for tariff preferences or faces scrutiny abroad.

On July 8, 2025, Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade (MoIT) issued a consolidated circular on rules of origin, which combined previous directives on the framework in Vietnam. According to the circular, Vietnam’s rules of origin follow two key principles:

Local value content

A product must derive a minimum portion of its value from materials sourced and processing carried out within Vietnam. This ensures that sufficient local economic activity contributes to the final product’s value.

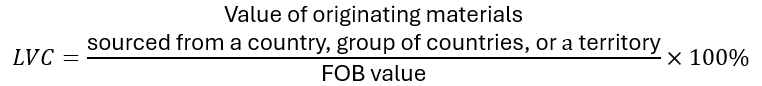

These are the two formulas used to calculate the Local Value Content (LVC), as defined under Vietnam’s trade agreements:

- Direct method:

- Indirect method:

Where:

- FOB value (Free on Board) refers to the price of goods delivered on board at the port of export, including domestic transport, packaging, and loading costs.

- Originating materials are those produced within Vietnam or within a partner country under the relevant free trade agreement.

- Non-originating materials are imported inputs from countries outside the agreement’s coverage.

Change in tariff classification

The Change in Tariff Classification (CTC) criterion refers to a modification in the Harmonized System (HS) code of a finished product – at the 2-digit, 4-digit, or 6-digit level – compared with the HS code of the non-originating input materials (including imported or indeterminate-origin components) used in its production. Such a change serves as evidence that a substantial transformation has occurred during processing in the country of manufacture.

In practice, non-originating inputs must undergo a transformation that alters their tariff classification, typically at the 4-digit (heading) level of the HS code, to confirm that a significant manufacturing process has taken place in Vietnam. This transformation results in a new product with a distinct classification, thereby conferring local origin status under applicable trade and customs rules.

Vietnam Introduces Decree on Strategic Trade Controls

Issued on October 10, 2025, Decree 259/2025/ND-CP introduces Vietnam’s first comprehensive framework for managing the export, re-export, temporary import, transit, transshipment, and cross-border movement of strategic trade goods. These include weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), conventional arms, and dual-use items – goods normally intended for civilian purposes but potentially usable in developing or producing WMDs or conventional weapons.

The decree establishes key management principles, requiring all strategic trade goods to comply with relevant laws on foreign trade, taxation, customs, and sectoral regulations. Traders handling dual-use goods must obtain an export or transit license, except for use in national defense or security. Licensing is also mandatory when there are reasonable suspicions that a shipment could be used to produce WMDs or that the end-user appears on a designated sanctions list, even if the goods are not explicitly listed as dual-use. The Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) may further extend licensing requirements to other goods to fulfil international obligations or bilateral agreements.

Proof of origin under Vietnam regulations

Certificates of Origin

In Vietnam, Certificates of Origin (C/O) are issued through the eCoSys system. The platform is managed by the Agency for E-commerce and Digital Economy, which oversees the technical infrastructure and ensures data connectivity with Vietnam’s National Single Window portal. The agency is also responsible for creating user accounts, assigning identification codes to authorized issuing bodies, and maintaining an up-to-date public directory of these entities on eCoSys.

For further information on C/O application in Vietnam, please read: How to Apply for a Certificate of Origin in Vietnam

Certificate of Non-Manipulation

The application for a Certificate of Non-Modification of Origin (CNM) is managed through the MoIT’s eCoSys system. The detailed steps are as follows:

Step 1: Register trader profile

Exporters must first register as a “trader” in the eCoSys system or submit registration documents in person at the authorized C/O issuing body.

Step 2: Submit CNM application

Once registered, the trader attaches the application dossier on eCoSys; alternatively, the dossier can be submitted in person or by post to the issuing authority where the trader’s profile is registered.

Step 3: Preliminary review

The issuing authority evaluates the completeness and validity of the application. It may ask the applicant to:

- Provide missing documents (specifying which ones)

- Provide or correct minimum mandatory information for the CNM

- Or outright refuse the application if:

- The trader has not completed trader registration per Article 13 of Decree No. 31/2018/ND-CP (“Decree 31”);

- The application dossier fails to meet the requirements of Article 19(2) of Decree 31 or contains inconsistent information

- The trader has outstanding documents (“debt”) from prior CNM issuance

- The trader was previously found to have committed origin fraud in a prior CNM case, not yet resolved

- The CNM form is improperly filled (e.g., with red ink, hand-written, tampered, illegible, or multiple ink colors)

Step 4: Data entry and submission for approval

If the dossier passes the preliminary check, staff input the data into the system and forward the application to the authorized signatory.

Step 5: Signing of CNM

Decision-making authority at the issuing body signs the CNM.

Step 6: Seal and delivery

The issuing authority affixes its official seal and returns the approved CNM to the trader.

To obtain CNMs, applicants must submit (one set) documentation, including:

- Trader registration dossier (signature specimen, corporate registration, list of production sites, etc.);

- CNM application form (per Decree 31/2018 and Circular 05/2018);

- The originally issued C/O from the first exporting country;

- Copy of the bill of lading or equivalent transport document (certified); and

- Copy of import/export customs declarations or internal warehouse declarations with customs certification.

The process timeframe can vary in certain cases:

- For complete and valid electronic applications: decision is made within six working hours after receipt;

- For paper applications properly submitted via eCoSys: decision within two working hours;

- For direct in-person submissions: within eight working hours; and

- For postal submissions: within 24 working hours from the date of receipt at the issuing body.

Case studies: Which sectors are most vulnerable to origin risks?

For Vietnam’s exports, origin fraud can happen in various sectors, especially in electronics, garments, footwear, bicycles, wood, iron and steel, and solar panel products.

Case 1: US anti-dumping and countervailing duties on Vietnam’s solar panels

In April 2025, the US Department of Commerce (DOC) imposed final anti-dumping and countervailing duties of up to 542.64 percent on Vietnamese-made solar cells and panels. The ruling concluded that certain Vietnamese exporters had sold products in the US market at unfairly low prices and benefited from subsidies tied to Chinese parent companies.

The DOC’s investigation determined that several Chinese-owned manufacturers had relocated or expanded operations in Vietnam to assemble or process solar components – actions that effectively circumvented existing US tariffs on Chinese imports. Although these facilities were formally registered in Vietnam, they were found to depend heavily on Chinese inputs, equipment, and managerial oversight, thereby failing to meet the substantial transformation test required under US trade regulations.

With this decision, Vietnam joins three other Southeast Asian countries accused of facilitating tariff evasion through transshipment or minimal processing. The outcome significantly elevates compliance risks for Vietnam’s solar sector – one of its fastest-growing export industries – now subject to intensified US scrutiny over origin verification and supply chain transparency.

Case 2: US$4.3 billion aluminum origin fraud

In 2019, Vietnamese authorities uncovered a major origin fraud case involving 1.8 million tons of aluminium falsely labeled as “Made in Vietnam” and destined for the US market. The shipment, valued at approximately US$4.3 billion, was detected by Vietnam Customs during an inspection of a company based in Ba Ria-Vung Tau Province.

The company operated legitimate manufacturing facilities but was found to have imported semi-finished aluminium products from China and other markets, which were subsequently re-exported to the United States under false Vietnamese origin claims. The scheme sought to evade US tariffs of up to 374 percent on Chinese aluminium by exploiting Vietnam’s comparatively low 15 percent export tax rate at the time.

This case shows the scale and sophistication of origin fraud risks emerging alongside Vietnam’s growing export volumes and reinforces the need for enhanced customs monitoring and corporate due diligence to ensure origin integrity in cross-border trade.

Case 3: Hai Phong export processing company’s origin fraud scheme

Also in 2019, customs authorities in Hai Phong uncovered a case involving a wholly foreign-invested export processing company suspected of falsifying product origin. The company imported spare parts from China, performed only minimal assembly in Vietnam, and then exported the finished goods to a third country under a “Made in Vietnam” label. According to customs officials, this practice constituted an attempt to evade origin rules and benefit from preferential tariff treatment reserved for genuine Vietnamese products.

Takeaway for businesses

Given the 40 percent tariff rate on transshipments from third countries, exporters operating in Vietnam must take proactive steps to ensure compliance and manage exposure to trade risks. While the US government is intensifying its scrutiny of trade practices, particularly regarding transshipment and origin fraud, the absence of detailed enforcement guidance presents an added layer of uncertainty for businesses.

In this evolving environment, companies should prioritize genuine manufacturing operations in Vietnam rather than relying on minimal processing of Chinese inputs to qualify for preferential treatment. By strengthening supply chain transparency, maintaining robust documentation, and aligning with rules-of-origin requirements, firms can not only mitigate compliance risks but also leverage Vietnam’s position as a credible manufacturing base to gain a competitive edge in the shifting global trade landscape.

About Us

Vietnam Briefing is one of five regional publications under the Asia Briefing brand. It is supported by Dezan Shira & Associates, a pan-Asia, multi-disciplinary professional services firm that assists foreign investors throughout Asia, including through offices in Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and Da Nang in Vietnam. Dezan Shira & Associates also maintains offices or has alliance partners assisting foreign investors in China, Hong Kong SAR, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Mongolia, Dubai (UAE), Japan, South Korea, Nepal, The Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Italy, Germany, Bangladesh, Australia, United States, and United Kingdom and Ireland.

For a complimentary subscription to Vietnam Briefing’s content products, please click here. For support with establishing a business in Vietnam or for assistance in analyzing and entering markets, please contact the firm at vietnam@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com

- Previous Article Green Incentives and Preferable Policies in Vietnam: An Overview for Investors

- Next Article Vietnam Reclassified to Emerging Market Status by FTSE Russell